Artworks… We talk about them, comment on them; they are analysed, criticised, and dissected. Although we rarely make a habit of it, today we are giving a voice to one artwork from our collections. Flattered by this sensitive attention, a young woman, represented by the Head of a Young Peasant Woman, will describe the care and attention she has enjoyed in lavish detail.

LET’S GET ACQUAINTED

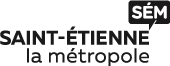

If you have recently visited the Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole, you might recognise me. I am an unnamed young woman painted by an eighteenth-century artist, who is also anonymous. I have resided in Saint-Étienne since 1893.

I go by the name of Head of a Young Peasant Woman. I find that a bit reductive, since you can see much more than my face and are you sure that I’m a woman of the fields? My attire could also be that of a servant. But all in all, that’s of little importance. What will be clear to you now is that I am a woman of the people. In the eighteenth century, artists adored painting us in a picturesque and charming manner. Am I not picturesque and charming?

A DECISIVE ENCOUNTER

Recently people came to pay me visit in the storeroom of the museum where I hold court on a grid, in the company of other paintings from my century.

They scrutinised me from every angle. I was embarrassed, because I was really not presentable. But I learned on this occasion that I was going to be shown in public at an exhibition about Maurice Allemand, the former director of the Musée d’Art et d’Industrie de Saint-Étienne. I was overjoyed about that because I knew his wife Geneviève well. She took care of me in 1965. She discovered at that time that they’d made a mistake about me.

I am not a painting on canvas, but in actual fact a painting on paper. But Geneviève Allemand was a secretive one, because she concealed the zones where paper and canvas meet. Her work was discreet, but if you look carefully at this photo of me, you will see a difference between the intense black of the canvase (on the right) and the black pitted with white on the paper (on the left).

Towards the mid-nineteenth century, I was backed: meaning pasted onto a canvas. From a rectangular format, I became oval and received this magnificent gilded wooden frame. I adore the finesse of its wreaths, which I endlessly contemplate.

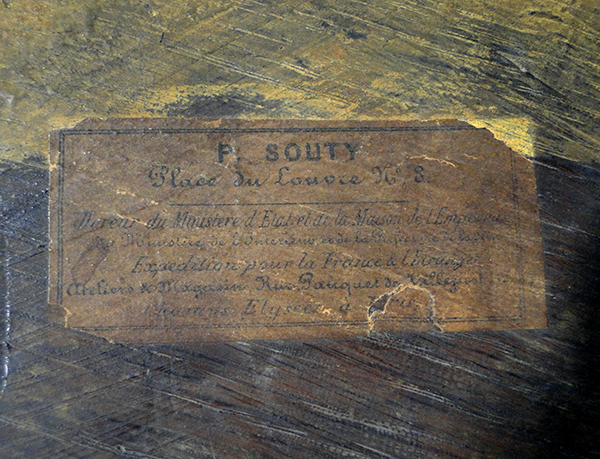

I believe I owe this magnificent adornment to Monsieur Souty, a painter and gilder from Paris, under Napoleon III. In fact, he left his business card on my back.

PREPARATION

I was fortunate enough to enjoy delicate attentions so as to look my best. To achieve this, I was stripped of my frame. What a strange sensation!

My back was dusted and the accumulated deposits from between my canvas and frame were removed. It was high time, because they were becoming painful and starting to deform my canvas.

I recovered my light colouring and the pink of my cheeks thanks to a cleaning session. I was not reassured; I did not take my eyes off the restorer.

This treatment was beneficial and helped to attenuate the cracks in my varnish, the whitish veil that covers me. The curls in my hair recovered their blondness against the dark background.

My right ear presented an unattractive lifting of the varnish. Fortunately everything was put back in place.

Finally, to my great chagrin, my varnish coating had yellowed, leaving traces of streaks. I was unhappy, because my entire chest was covered with them. There too, the result exceeded my expectations. I will show you, but don’t linger for too long on my plunging neckline!

Before putting me back in my frame, they took care to cover the rabbet with a canvas ribbon. The rabbet is the little shelf on the frame I’m inserted onto. The raw wood was endlessly provoking scratches at my edges.

Here I am ready to head for the exhibition rooms!

Even though I remain anonymous, I hope that I am no longer a stranger in your eyes. Come pay me a visit at the exhibition Maurice Allemand: Or How Modern Art Came to Saint-Étienne (1947–1966). I would be delighted. I will be in residence until 3 January 2021.

The Young Peasant Woman

PS: I address here my heartfelt thanks to my restorer, Julie Barth.

Nombre de commentaires